How will OpenAI compete?

“Jakub and Mark set the research direction for the long run. Then after months of work, something incredible emerges and I get a researcher pinging me saying: “I have something pretty cool. How are you going to use it in chat? How are you going to use it for our enterprise products?”

- Fidji Simo, head of Product at OpenAI, 2026

“You've got to start with the customer experience and work backwards to the technology. You can't start with the technology and try to figure out where you're going to try to sell it”

- Steve Jobs, 1997

It seems to me that OpenAI has four fundamental strategic questions.

First, the business as we see it today doesn’t have a strong, clear competitive lead. It doesn’t have a unique technology or product. The models have a very large user base, but very narrow engagement and stickiness, and no network effect or any other winner-takes-all effect so far that provides a clear path to turning that user base into something broader and durable. Nor does OpenAI have consumer products on top of the models themselves that have product-market fit.

Second, the experience, product, value capture and strategic leverage in AI will all change an enormous amount in the next couple of years as the market develops. Big aggressive incumbents and thousands of entrepreneurs are trying to create new features, experiences and business models, and in the process try to turn foundation models themselves into commodity infrastructure sold at marginal cost. Having kicked off the LLM boom, OpenAI now has to invent a whole other set of new things as well, or at least fend off, co-opt and absorb the thousands of other people who are trying to do that.

Third, while much of this applies to everyone else in the field as well, OpenAI, like Anthropic, has to ‘cross the chasm’ across the ‘messy middle’ (insert your favourite startup book title here) without existing products that can act as distribution and make all of this a feature, and to compete in one of the most capital-intensive industries in history without cashflows from existing businesses to lean on. Of course, companies that do have all of that need to be able to disrupt themselves, but we’re well past the point that people said Google couldn’t do AI.

The fourth problem is expressed in the quotes I used above. Mike Krieger and Kevin Weil made similar points last year: when you’re head of product at an AI lab, you don’t control your roadmap. You have very limited ability to set product strategy. You open your email in the morning and discover that the labs have worked something out, and your job is to turn that into a button. The strategy happens somewhere else. But where?

OpenAI does still at least arguably set the agenda for new models, and it has a lot of great technology and a lot of clever and ambitious people. But unlike Google in the 2000s or Apple in the 2010s, those people don’t have a thing that really really works already that no-one else can do. I think that one way you could see OpenAI’s activity in the last 12 months is that Sam Altman is deeply aware of this, and is trying above all to trade his paper for more durable strategic positions before the music stops.

Let’s start with the models.

There are many benchmarks, all of them ‘wrong’, but they all show the same picture

There are something like half a dozen organisations that are currently shipping competitive frontier models, all with pretty-much equivalent capabilities. Every few weeks they leapfrog each other. There is variation within those capabilities, it’s possible to drop off the curve (Meta, for now) or fail to get onto it (Apple, Amazon, Microsoft, for now), or remain six months behind the frontier (China), or rely heavily on other people’s work (China, again) and all of this needs a lot of money (of which more below), but today there is no mechanic we know of for one company to get a lead that others in the field could never match. There is no equivalent of the network effects seen at everything from Windows to Google Search to iOS to Instagram, where market share was self-reinforcing and no amount of money and effort was enough for someone else to to break in or catch up.

This could change if there was a breakthrough that enabled a network effect, most obviously continuous learning, but we can’t plan for that happening. It could also change if there are practical scale effects around access to proprietary data, which today is the dark matter of AI: this could be user data (but it’s not clear what scale here would look like, and the existing platform companies have a lot), or vertical data (foundation models don’t know what happens inside SAP or Salesforce and don’t have millions of spreadsheets from inside investment banks, though you can sometimes buy this or pay people to make it, but so can all the other big players). There might be something else here as well, but at the moment we don’t know and you can’t plan for it, so we have to presume that the models will remain very close for the time being.

The one place where OpenAI does have a clear lead today is in the user base: it has 8-900m users. The trouble is, there’re only ‘weekly active’ users: the vast majority even of people who already know what this is and know how to use it have not made it a daily habit. Only 5% of ChatGPT users are paying, and even US teens are much more likely to use this a few times a week or less than they are to use it multiple time a day. The data that OpenAI released in its ‘2025 wrapped’ promotion tells us that 80% of users sent less than 1,000 ‘messages’ in 2025. We don’t know how that changed in the year (it probably grew) but at face value that’s an average of less than three prompts per day, and many fewer individual chats. Usage is a mile wide but an inch deep.

This means that most people don’t see the differences between model personality and emphasis that you might see, and most people aren’t benefiting from ‘memory’ or the other features that the product teams at each company copy from each other in the hope of building stickiness (and memory is stickiness, not a network effect). Meanwhile, usage data from a larger (for now) user base itself might be an advantage, but how big an advantage, if 80% of users are only using this a couple of times a week at most?

This engagement is a clearly a ‘glass half full or half empty?’ question, but this is supposed to be a transformation in how you use computers. If people are only using this a couple of times a week at most, and can’t think of anything to do with it on the average day, it hasn’t changed their life. OpenAI itself admits the problem, talking about a ‘capability gap’ between what the models can do and what people do with them, which seems to me like a way to avoid saying that you don’t have clear product-market fit.

Hence, OpenAI’s ad project is partly just about covering the cost of serving the 90% or more of users who don’t pay (and capturing an early lead with advertisers and early learning in how this might work), but more strategically, it’s also about making it possible to give those users the latest and most powerful (i.e. expensive) models, in the hope that this will deepen their engagement. Fidji Simo says here that “diffusion and scale is the most important thing.” That might work (though it also might drive them to pay, or drive them to Gemini). But it’s not self-evident that if someone can’t think of anything to do with ChatGPT today or this week, that will change if you give them a better model. It might, but it’s at least equally likely that they’re stuck on the blank screen problem, or that the chatbot itself just isn’t the right product and experience for their use-cases no matter how good the model is.

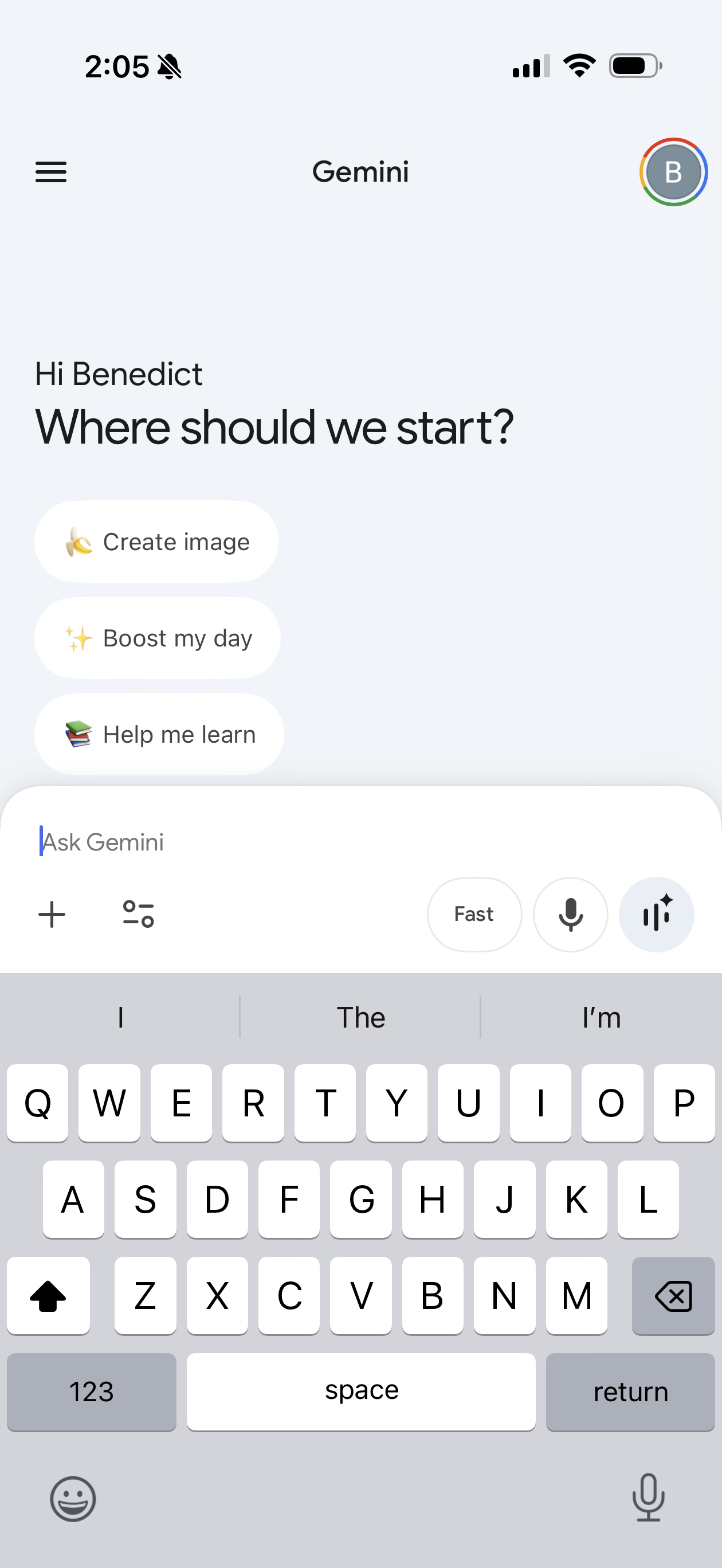

In the meantime, when you have an undifferentiated product, early leads in adoption tend not to be durable, and competition tends to shift to brand and distribution. We can see this today in the rapid market share gains for Gemini and Meta AI: the products look much the same to the typical user (though people in tech wrote off Llama 4 as a fiasco, Meta’s numbers seem to be good), and Google and Meta have distribution to leverage. Conversely, Anthropic’s Claude models are regularly at the top of the benchmarks but it has no consumer strategy or product (Claude Cowork asks you to install Git!) and close to zero consumer awareness.

This has led a lot of people to compare ChatGPT to Netscape, where Microsoft used distribution to crowbar its way into a market where the products themselves were hard to tell apart, much as Google and Meta do today.

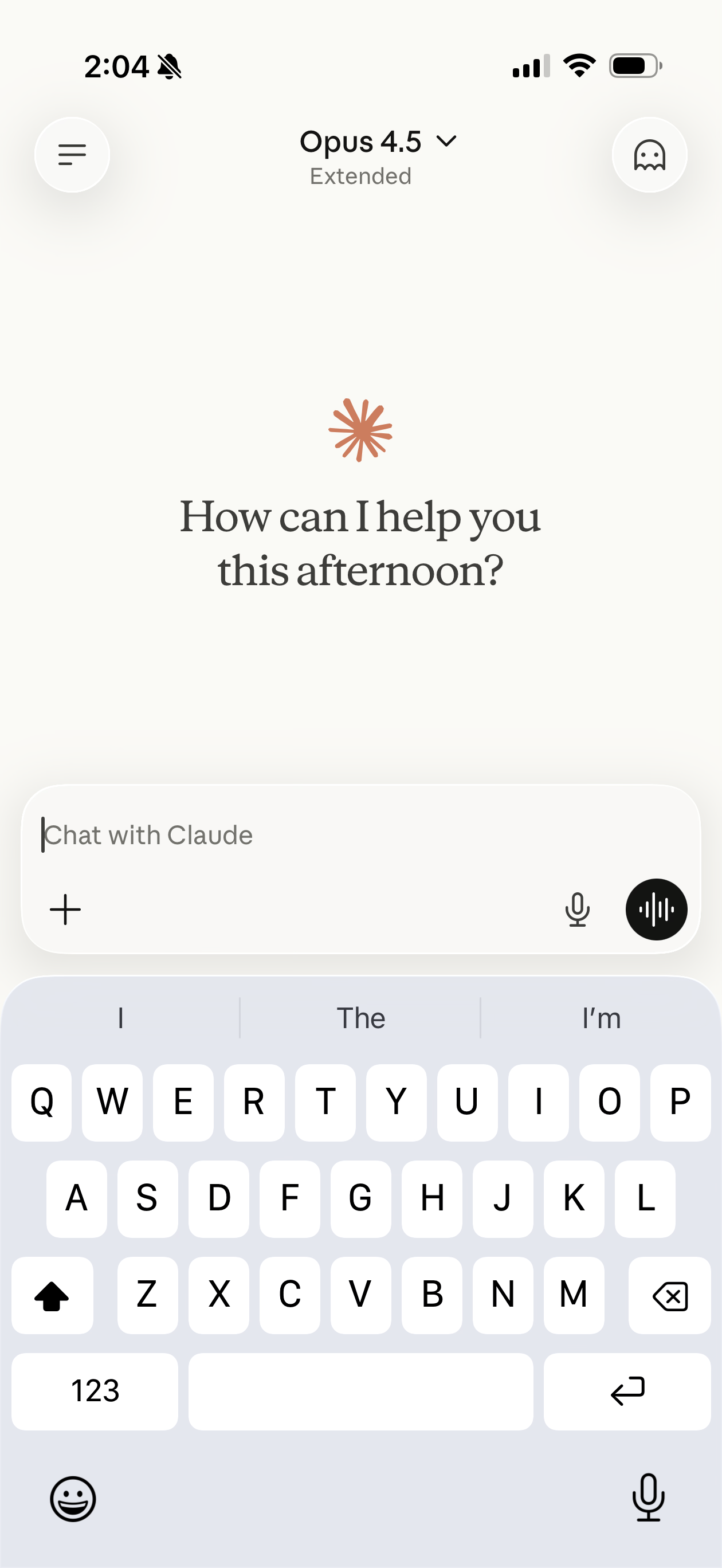

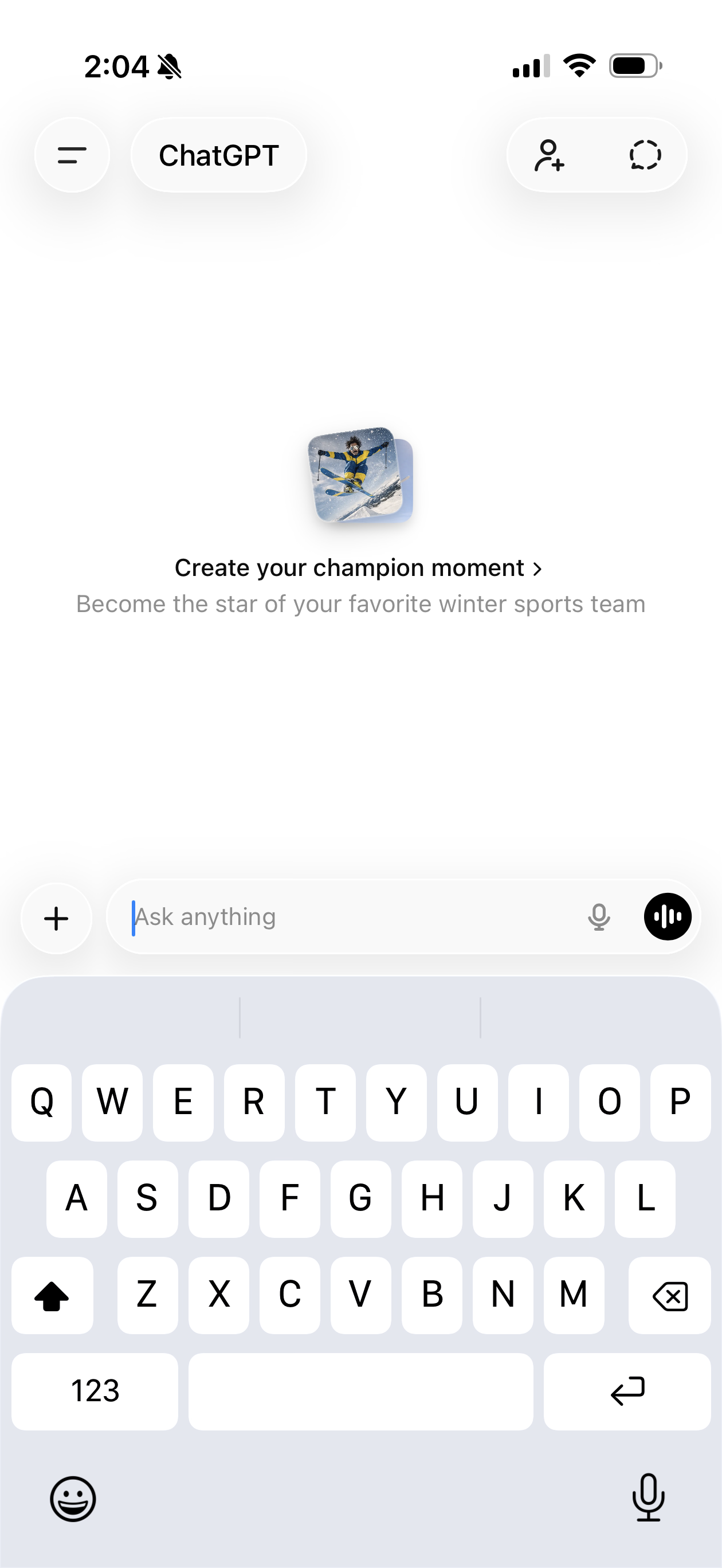

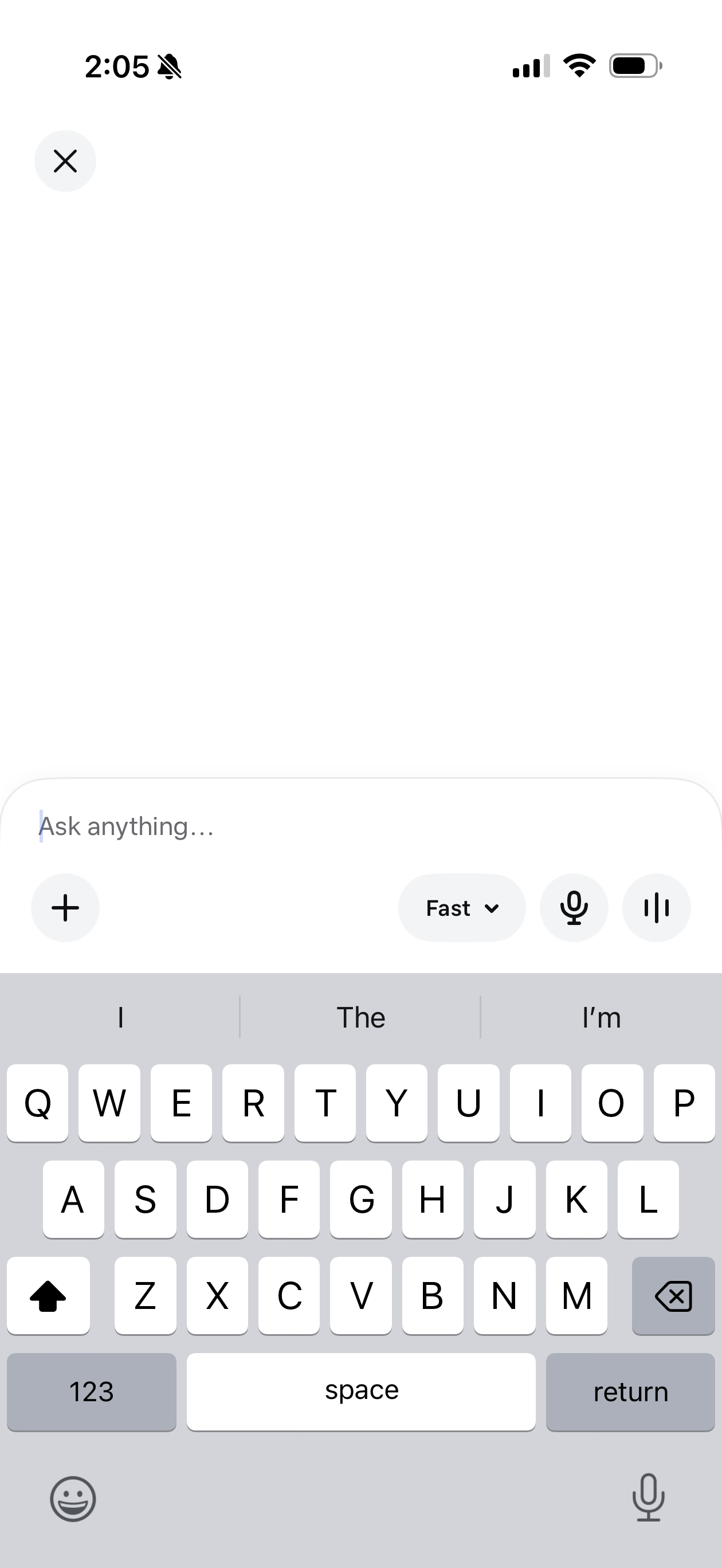

Taking this a step further, it’s interesting to compare how hard it was to differentiate a web browser with how hard it is today to differentiate a chatbot: this looks like the same problem. You can make the rendering engine better in a browser and you can make the LLM better in a chatbot, but the browser itself, and the chatbot itself, are just an input box and an output box. The ChatGPT app, like all the chatbot apps, is just a ‘thin wrapper’ - how could you make yours different? In browsers, the answer was that you couldn’t - the last successful product innovations were tabs and merging search with the URL bar. Chatbots today have the same problem - how many more little buttons can you add, and how can you tell them apart?

In the end, though, Microsoft won browsers for the first generation of the consumer internet but that turned out not to matter, because the experiences that did matter, and the value capture, were created elsewhere. Equally, the real question for the ‘engagement gap’ is whether this is solved through generalised model improvements that we must presume will apply across the entire industry, or innovation in the UI that, again, everyone will copy, or whether it is followed by the invention and creation of new experiments and use cases built on top of the ‘raw’ models.

If the next step is those new experiences, who does that, and why would it be OpenAI? The entire tech industry is trying to invent the second step of generative AI experiences - how can you plan for it to be you? How do you compete with this chart - with every entrepreneur in Silicon Valley?

So: you don’t know how you can make your core technology better than anyone else’s. You have a big user base but one that has limited engagement and seems really fragile. The key incumbents have more or less matched your technology and are leveraging their product and distribution advantages to come after the market. And, it looks like a lot of the value and leverage will come from new experiences that haven’t been invented yet, and you can’t invent all of those yourself. What do you do?

For a lot of last year, it felt like OpenAI's answer was “everything, all at once, yesterday”. An app platform! No, another app platform! A browser! A social video app! Jony Ive! Medical research! Advertising! More stuff I've forgotten! And, of course, trillions of dollars of capex announcements, or at least capex aspirations.

Some of this looked like ‘flooding the zone’, or at least just the result of hiring a lot of aggressive, ambitious people really quickly. There was also sometimes the sense of people copying the forms of previously successful platforms without quite understanding their purpose or dynamics: “platforms have app stores, so we need an app store!”

But late last year, Sam Altman tried to put it all together, showing this diagram, and using the famous quote from Bill Gates, that the definition of a platform is that it creates more value for its partners than for itself.

At much the same time, the CFO published this diagram.

PSA: a 1:1 relationship between capex and revenue is not a flywheel

This is a nice, neat, coherent strategy. Your capex is a virtuous circle in its own right, and it’s the foundation of a plan to build a full-stake platform company on top. You build every layer of the stack, from chips and infrastructure up, and the further you go up the stack, the more you help other people create their own things with your tooling. Everyone gets to use your cloud, your chips, your models, and then further up, the layers of the stack are mutually reinforcing. You have a network effect, you have an ecosystem, you have leverage up and down the stack, everyone builds on your stuff and everyone is locked in. Other people might built parts of that stack too, but you have a defensible, differentiated, value-capturing platform.

That is indeed how Windows or iOS worked. The trouble is, I really don't think that's the right analogy. I don't think OpenAI has any of this. It doesn’t have the kind of platform and ecosystem dynamics that Microsoft or Apple had, and that flywheel diagram doesn’t actually show a flywheel.

Let's start by talking about capex. This is the stuff that gets everybody's attention, because the tech industry has never contemplated such large numbers before. The big four cloud companies spent about $400 billion on infrastructure last year and have announced plans for at least $650 billion this year.

As we all know, OpenAI has been running around trying to join the club, claiming a few months ago to have $1.4tr and 30 gigawatts of compute commitment for the future (with no timeline), while it reported 1.9 gigawatts in use at the end of 2025. Since it doesn’t have the scale of cashflows from existing businesses that the hyperscalers can use, it has so far managed to do this, or at least announce this, with a combination of capital-raising (not all of which has necessarily closed) and other peoples balance sheets (some of which is also the famous ‘circular revenue’).

You can watch plenty of three-hour podcasts discussing all of this, and plenty of people have opinions about TPUs, Nvidia’s product lead, and Oracle’s strategy of borrowing against a declining but cash-generative legacy business to burn its way into the new thing, but how much should the rest of us care? Is this a path to a competitive advantage, or just a seat at the table?

We don’t really know what AI infrastructure costs will look like in the long term, but it’s quite possible that this turns out like the manufacture of airliners or semiconductors: there are no network effects, but with each generation the process gets more difficult and more expensive, and so those industries have gone from dozens of companies at the cutting edge to just Boeing and Airbus on one hand and TSMC on the other. Semiconductor manufacturing had both Moore’s Law, which everyone has heard of, and Rock’s Law, which most people haven’t: Moore’s Law said that the number of transistors on a chip was doubling every two years, but Rock’s Law said that the cost of a state-of-the-art semiconductor fab was doubling every four years. Maybe generative AI will work the same, with unit costs falling but fixed costs rising to the point that only a handful of companies are able to sustain the investment needed to build competitive models and everyone else is squeezed out.* This oligopoly would presumably have a price equilibrium, though it might be at high or low margins - this might all just be commodity infrastructure sold at marginal cost, especially given some of those at the table will be using their models to power other, much more differentiated businesses. Ask your favourite economist. **

So, when Sam Altman says he’s raised $100bn or $200bn, and when he says he’d like OpenAI to be building a gigawatt of compute every week (implying something in the order of a trillion dollars of annual capex), it would be easy to laugh at this as ‘braggawatts’, and apparently people at TSMC once dismissed him as ‘podcast bro’, but he’s trying to create a self-fulfilling prophecy. He’s trying to get OpenAI, a company with no revenue three years ago, a seat at a table where you’ll probably need to spend couple of hundred billion dollars a year on infrastructure, through force of will. His force of will has turned out to be pretty powerful so far.

But, again, does that get you anything more than a seat at that table? TSMC isn’t just an oligopolist - it has a de facto monopoly on cutting edge chips - but that gives it little to no leverage or value-capture further up the stack. People built Windows apps, web services and iPhone apps - they don’t build TSMC apps or Intel apps.

Developers had to build for Windows because it had almost all the users, and users had to buy Windows PCs because it had almost all the developers (a network effect!). But if you invent a brilliant new app or product or service using generative AI, or add it as a feature to an existing product, you use the APIs to call a foundation model running in the cloud and the users don’t know or care what model you used. No-one using Snap cares if it runs on AWS or GCP. When you buy an enterprise SaaS product you don’t care if it uses AWS or Azure. And if I do a Google Search and the first match is a product that’s running on Google Cloud, I would never know.

That doesn’t mean these APIs are interchangeable - there are good reasons why AWS, GCP and Azure have very different market shares, and why developers choose each. But the customer doesn’t know or care. Running a cloud doesn’t give you leverage over third part products and services that are further up the stack.

The difference now, perhaps, is that all of those services were separate silos: there was a common search and discovery layer at the top in Google and Facebook, and common infrastructures at the bottom in the cloud, but all those apps were never connected to each other. Now we have an emerging alphabet soup of standards and protocols for models and websites to talk to each other across ads, e-commerce and some kind of intent and automation (the brief enthusiasm around OpenClaw captured some of this). A website can surface its capabilities so that a subset can just show up in ChatGPT, be it a real estate search or a shopping cart. You’ll tell your agent to look at a recipe on Instagram and order the ingredients on Instacart. Everything can get piped to everything else, and everything can talk to each other!

Meanwhile, (saying the quiet part out loud), if you could set and control those APIs and manage the flows, that gives you power. Standards have been a basic competitive weapon in every generation of technology - remember Microsoft’s slogan ‘embrace and extend’. In particular, OpenAI suggests now suggests you’ll use your ChatGPT account as the glue linking all of these together. That’s a network effect!

I'm not sure about this: I’m not sure that this vision will really work, and if it does, I’m not sure it gives one company dominance.

First, there’s a recurring fallacy in tech that you can abstract many different complex products into a simple standard interface - you could call this the ‘widget fallacy’. A decade ago people said ‘APIs are the new BD’, which was really the same concept, and it mostly failed. This is partly because there’s a huge gap between what looks cool in demos and all of the work and thought in the interaction models and the workflows in the actual product: very quickly you’ll run into an exception case and you’ll need the actual product UI and a human decision. It’s also because the incentives are misaligned: no-one wants to be someone else’s dumb API call, so there’s an inherent tension or trade-off between the distribution that an abstraction layer might give you (Google Shopping, Facebook shopping, and now ChatGPT shopping) and your desire to control the experience and the customer relationship. Remember, after all, that all of Instacart’s profits come from showing ads.

Of course, this is just speculation - maybe it will all work this time! But the second problem is that if these are all separate systems plugged together by abstracted and automated APIs, is the user or developer locked into any one of them? If apps in the chatbot feed work, and OpenAI uses one standard and Gemini uses another, why stops a developer doing both? This is much less code than making both an iOS and Android app, and anyway, can’t you get the AI to write the code for you? What does that do to developer lock-ins? Meanwhile, yes, maybe I’ll log into all of these services with my OpenAI or Gemini account, but does it necessarily make sense for me to log into Tinder, Zillow and Workday with the same account? And, again, do they want that?

Hmm.

As I've written this essay, I’ve returned again and again to terms like platform, ecosystem, leverage and network effect. These terms get used a lot in tech, but they have pretty vague meanings. Google Cloud, Apple's App Store, Amazon Marketplace, and even TikTok are all ‘platforms’ but they're all very different.

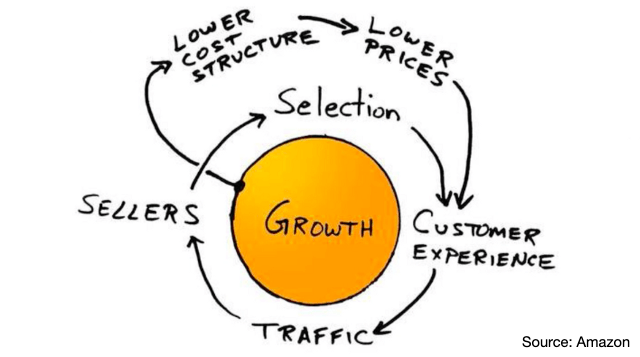

Maybe the word I'm really looking for is power. When I was at university, a long time ago now, my medieval history professor, Roger Lovatt, told me that power is the ability to make people do something that they don't want to do, and that's really the question here. Does OpenAI have the ability to get consumers, developers and enterprises to use its systems more than anybody else, regardless of what the system itself actually does? Microsoft, Apple and Facebook had that. So does Amazon - this is a real flywheel. ***

To this point, I think a good way to read that Bill Gates quote is that what a platform really achieves is to harness the creative energy of the entire tech industry, so that you don’t have to invent everything yourself and massively more stuff gets built at massive scale, but, it’s all done on your system with you holding the reins. Do LLMs have that?

Foundation models are certainly multipliers: massive amounts of new stuff will be built with them. But do you have a reason why everyone has to use your thing, even though your competitors have built the same thing? And are there reasons why your thing will always be better than the competition no matter how much money and effort they throw at it? That's how the entire consumer tech industry has worked for all of our lives. If not, then the only thing you have is execution, every single day. Executing better than everyone else is certainly an aspiration, and some companies have managed it over extended periods and even persuaded themselves that they’ve institutionalised this, but it’s not a strategy.

* Another comparison is the ‘capital as a weapon’ stage in ZIRP, when companies used cheap capital to buy their way to scale in the hope that would give them market dominance with a network effect that would be defensible. This worked at least arguably for Uber, but didn’t for WeWork which, like OpenAI, had no network effect.

** It’s also possible that this turns out completely differently and (say) that we end up with a huge number of models of many different shapes and sizes, some of which run on the edge for free, and talking about an oligopoly of AI infrastructure makes as much sense as talking about an oligopoly of SQL infrastructure. We just don’t know.

*** The counter to this is that Microsoft, Google, Apple and Meta may have lived in a world of ‘winner-takes-all’ effects, but they never thought they’d won. They were alway looking over their shoulder. The iconic expression of this mentality, of course, is Andy Grove’s quote that ‘only the paranoid survive’. Intel had a network effect, and then it didn’t, and it had a technology lead, and then it didn’t.